This post originally appeared on my substack.

Recently, I received a response to my blog about the secular rate of profit by Jehu, one of the more interesting Marxists operating online today. While I think that certain of his fixations, specifically on gold as a measure of value, are somewhat illogical, he has one of the most important political programs on the left today with his incessant drumbeat raising awareness about the need to decrease the length of the working day. His chief criticism of my blog, however, relates to this issue of gold as a measure of value, as he says what my analysis missed was how, while the rate of profit might have slightly recovered from the 70s profitability crisis in neoliberalism, the mass of profit has continued to decrease.

Jehu comes to this conclusion by converting the mass of profit, which is to say the total rather than percentage amount, into gold as a method of deflating the price into a constant measure. Thus, he argues, while an ideal capitalist earning 30% on their money capital both today and 60 years ago in 1962 might earn the same profit in nominal terms, the real value, the equivalent ounces of gold they’d be able to purchase with that amount, would be far less. He even notes the material reasons for why this is the case, that gold has become much more difficult to mine as all the easiest locations have all been extracted, and thus we’re turning to more expensive labor and capital intensive techniques to get what gold remains.

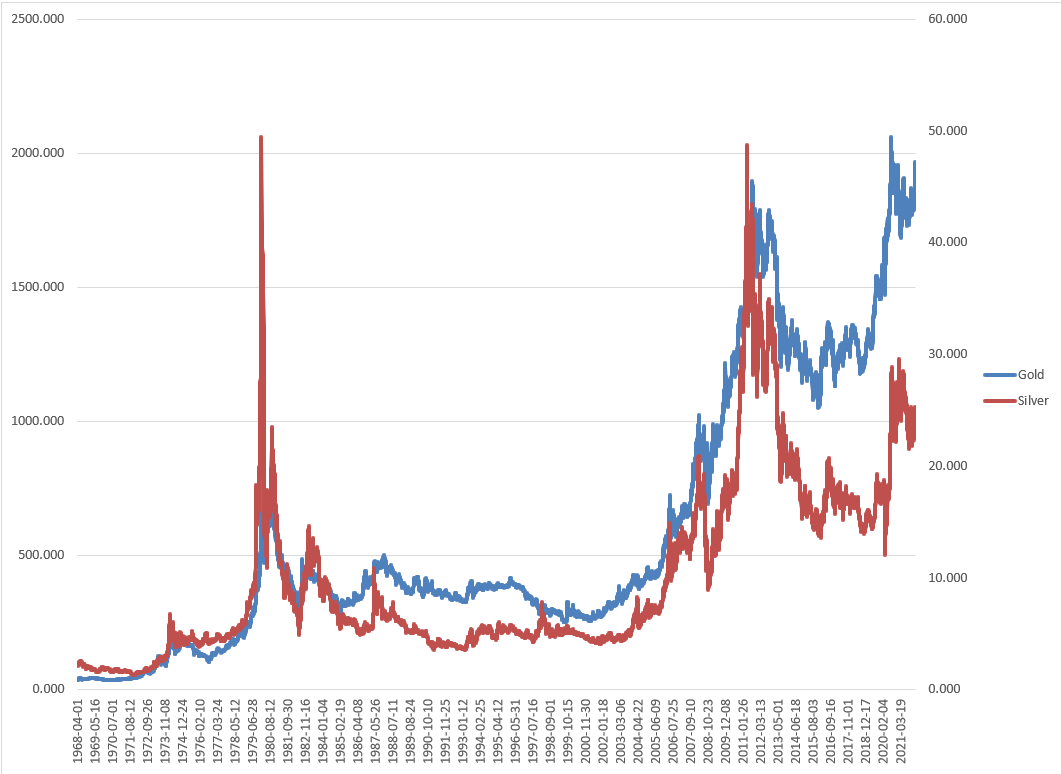

But choosing gold as the measure of value, as the ideal commodity money, is I think a form of cherry picking, one which can only be defended textually in Marx due to the historical coincidence of it being the primary form of commodity money at the time of his writing. For sure, other commodities have seen their value greatly increase due to the same extractive dynamics. Seafood is much more expensive than 200 or 300 years ago due to overfishing, (a plate of fried fish is roughly 5 times more expensive than the inflation adjusted price in 1830 would suggest). It’s also true of other minerals such as copper or rarer elements like cobalt. In comparison, many other commodities, particularly manufactured goods and electronics, have seen remarkable falls in value due to increasing labor productivity.

If we were to take silver, which was also used as money, the deflated graph would indeed look very different due to several points of divergences in the two prices. Indeed, the silver graph, due to the lower values more recently, would make the mass of profit look much better.

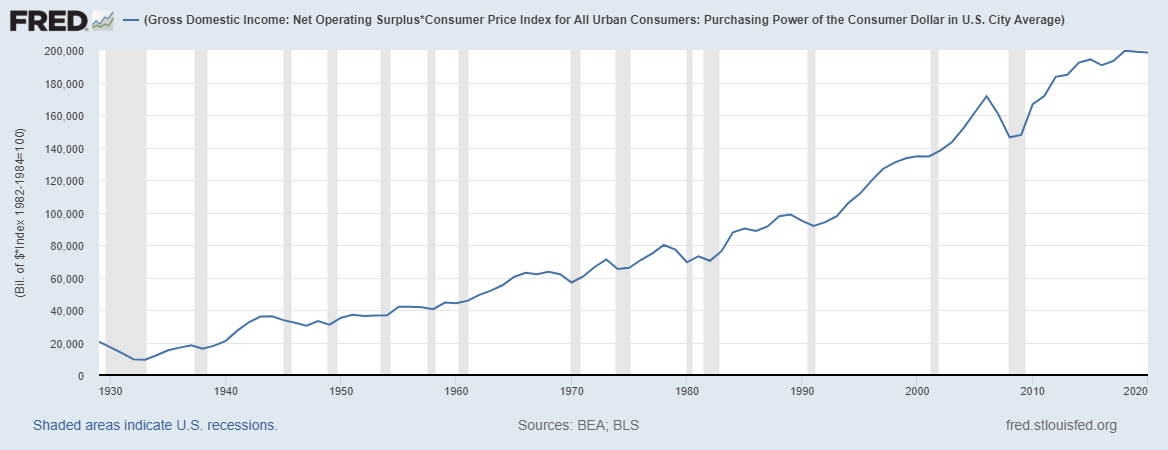

Now, given the great problems with using a single commodity to deflate prices, how should we go about creating a consistent measure of the mass of profit? There are broadly two options available. One, we can deflate prices using several different commodities which are commonly consumed for subsistence at the same time, this is effectively what modern economists do with inflation indexes. Using this measure, we see a remarkably linear increase in the mass of profit over time.

Like all of my graphs, this one can be found saved as a customized dataset on the Fred website. If you want to manipulate the data for yourself, you can hit download and download it as an excel dataset, or click on the source pages below the graphs and download individual datasets from there.

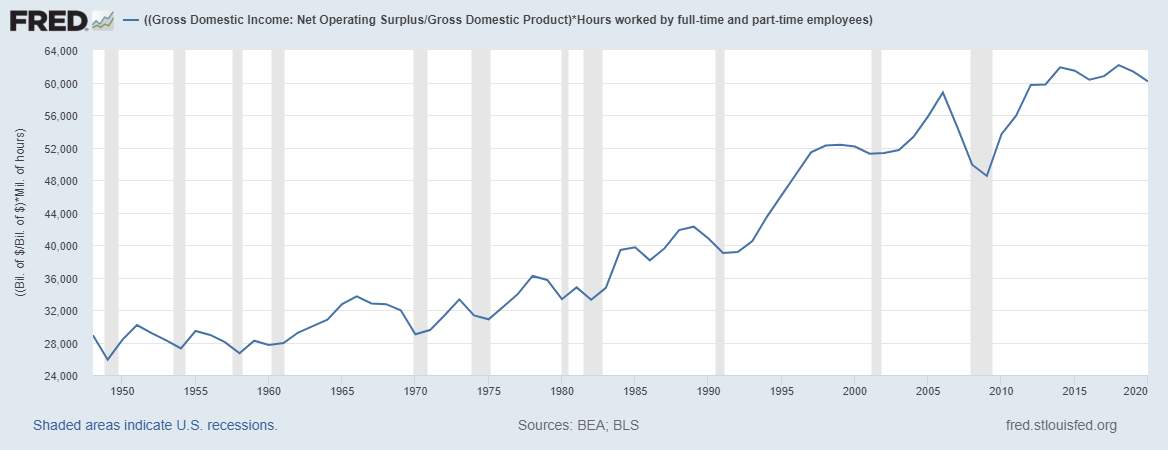

However, these CPI metrics are of course somewhat biased to the priors of neoclassical economics due to the training of the economists who create them, as I’m sure that Jehu would point out. So, I think a third option is required, one that cuts out the mediation through money entirely. While profit is expressed in fiat dollar terms, we can know what percent of total value is surplus value. This can be accomplished most simply by dividing GDP by net operating surplus, as net operating surplus is one of the line items in the national accounts that make up GDP. As any good Marxist can tell you, labor is the main determinant of value, the other main determinant being nature itself. Money, as Adam Smith put it, is simply the ability to command labor, and we can think about the various sources of income in society, such as wages and profit, and their proportion as ways of cutting the pie of society’s labor budget at any given time. So, in order to calculate the mass of profit, we can take the proportion of profit as a percent of total value, and then multiply that with the total hours worked in production.

That gives us this graph, which is also increasing linearly:

This linear increase in the mass of profit shouldn’t surprise us, because, as Marx informs us in Capital volume 1, “The mass of the surplus-value produced is therefore equal to the surplus-value which the working day of one labourer supplies multiplied by the number of labourers employed.” Which is to say, an increase in the number of workers must also increase the mass of surplus value, assuming a constant profit share of value created.

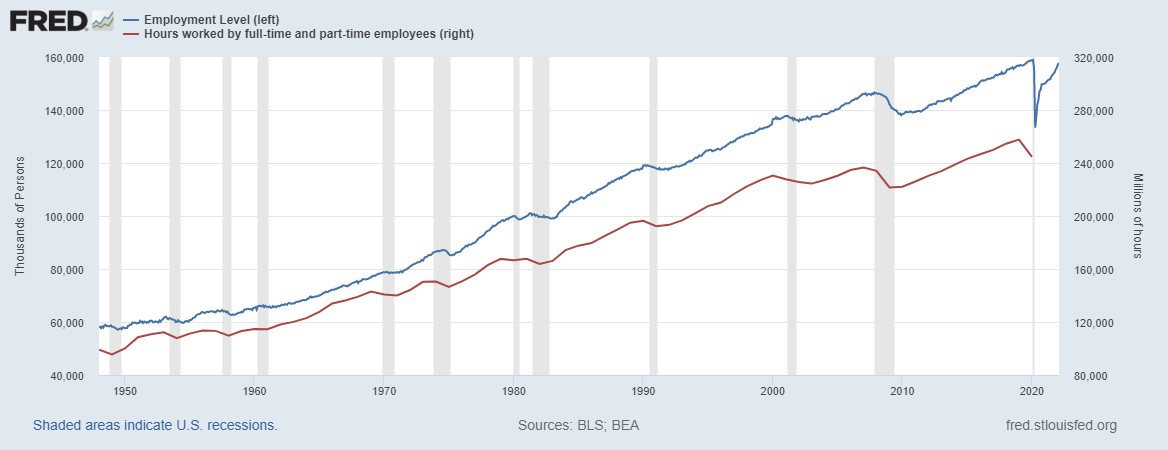

And an increase in the number of workers is exactly what we have seen, as well as an increase in the total hours worked each year.

Given this fundamental fact about how the mass of surplus value operates, I don’t think it’s appropriate to speak of a decline in such a mass until we see a secular decline in population and hours worked.

And while, yes, the American regime of neoliberalism has been remarkably effective in stabilizing the rate of profit here, we have just received new studies showing how the rate of profit has seriously declined globally (two facts that are probably not unrelated).

Now, it was mentioned earlier that the other source of value was nature, and it’s possible to see another argument here, that because of natural resource rents the mass of surplus value is decreasing, which requires us to exclude the profits of these industries from surplus in our calculations. However, it does not seem that this is something Jehu is calling for, and indeed such a severe increase in rent to natural resource extractors to counteract the increase in population and total working hours seems implausible.

Marx, for his part, seemed much more focused on the rate of profit than the mass for similar reasons. The history of industrialization has been the history of vast population growth and expansion of production, which, absent a sharp decrease in the rate of profit, does entail an ever growing mass. It’s also why, in volume three, he’s always cautioning us that a secular tendency for a falling rate of profit is compatible with an ever increasing mass of profit. The rate of profit, after all, combined with the level of real investment required by production, determines how much money capital an ideal capitalist needs before being able to subsist on their earnings. It determines the health of the capitalist class, and its ability to reinvest in production and cultivate the productive forces. This tendency for the rate of profit to fall also matters greatly, as it arrests the ability for capitalism to reproduce the capitalist class, leads to crises, and limits the ability for capitalist societies to stave off class conflict.

A declining mass of profit may yet become important, as we begin to deal with the problems of demographic transition leading to a shrinking population, changing the balance of power between capitalist empires and forcing more of surplus to be used towards taking care of the old. But, until then, I hope that Jehu reconsiders his position, and appreciates the importance of the rate of profit over the mass.